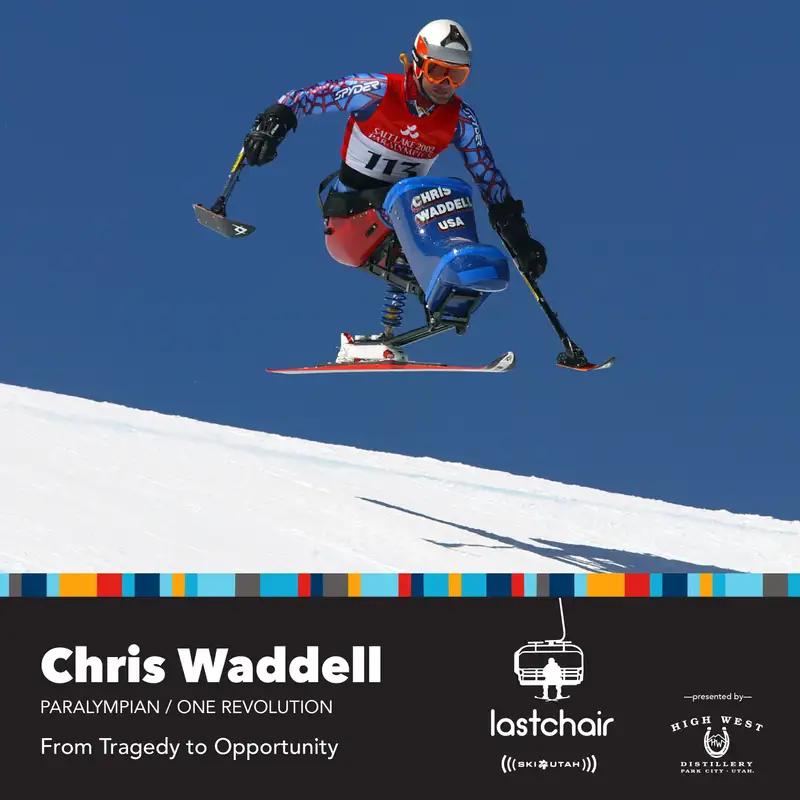

S2:Ep4. Chris Waddell: Tragedy To Opportunity

Lifelong skier and collegiate racer Chris Waddell was at the peak of his career when a skiing accident took away functionality of the lower half of his body. Just 362 days later, he was back on snow - this time in a monoski. One of the most decorated Paralympic athletes, Waddell today is an inspiration - like the rest of us, still aspiring for those deep powder Utah days near his adopted home!

Like many of us, Chris Waddell loves the feeling of being atop Bald Mountain at Deer Valley Resort. The distant peaks of the snow capped High Uintas are off to the right. To the left is the panoramic ridgeline of Park City. Below him is a pristine piste that is ready to be carved.

But instead of standing on two skis to admire the view, he sits in a fiberglass monocoque called a monoski. As the term implies, below him is a single ski, firmly attached to his plastic cockpit. With a push, he's off, wind in his face, his upper body maneuvering the monoski as he puts down some of the prettiest turns in the mountain as skiers stand transfixed by the scene.

Lifelong skier and collegiate racer Chris Waddell was at the peak of his career when a skiing accident took away functionality of the lower half of his body. Just 362 days later, he was back on snow - this time in a monoski. One of the most decorated Paralympic athletes, Waddell today is an inspiration - like the rest of us, still aspiring for those deep powder Utah days near his adopted home!

Chris Waddell's story is not one of great tragedy at the age of 20, but more the inspiration he has brought as one of the world's great athletes.

A Massachusetts native, Waddell moved to Utah full time in 1999 to train for the 2002 Olympics and, like many others, to ski the greatest snow on earth. Last Chair caught up with him in his temporary Bear Lake house, still pensively waiting for renovations to his ski town home in Park City.

WITH CHRIS WADDELL

Chris how did you find your way into skiing?

I grew up in a town called Granby, Massachusetts, which was probably about 5,000 people in western Mass. We were the in-between of the Berkshires. Mount Tom was about ten minutes away - 680 feet of vertical, about half the height of the Empire State Building. And I saw the kids racing. I was six years old or something and I said, 'I want to do that.

I grew up in a town called Granby, Massachusetts, which was probably about 5,000 people in western Mass. We were the in-between of the Berkshires. Mount Tom was about ten minutes away - 680 feet of vertical, about half the height of the Empire State Building. And I saw the kids racing. I was six years old or something and I said, 'I want to do that.

What was your pathway as a ski racer?

I didn't go to a ski academy, I went to a prep school, which meant that we might get to train for an hour a day or something like that. And it was a much shorter season. And I felt like I'd never given myself the chance to see how good I could be as a ski racer. So going to Middlebury, in a lot of ways for me, was going to be my Olympics. It was going to be how I proved how good I could possibly be. And so I spent the whole fall really trying to somehow write a new narrative. And and so my goal every day was to push myself in dry land training to the point where I wanted to quit. Because if I quit and then moved a little bit beyond that, then it was new territory.

I didn't go to a ski academy, I went to a prep school, which meant that we might get to train for an hour a day or something like that. And it was a much shorter season. And I felt like I'd never given myself the chance to see how good I could be as a ski racer. So going to Middlebury, in a lot of ways for me, was going to be my Olympics. It was going to be how I proved how good I could possibly be. And so I spent the whole fall really trying to somehow write a new narrative. And and so my goal every day was to push myself in dry land training to the point where I wanted to quit. Because if I quit and then moved a little bit beyond that, then it was new territory.

But that suddenly changed in an instant!

The first day of Christmas vacation, I went home. My brother and I went to Berkshire East and met up with a bunch of the buddies. We all skied with a group. It was a warm, sunny day. It was like a spring day, 20th of December, slushy snow, which was completely unheard of. And we took a couple of runs, as the coach said, and I was testing a new pair of skis - hadn't been on them yet. And we were going to run slalom and we came down and went back to the race track and he wasn't there. So we decided we'd take one more run. And it was just kind of a strange thing. You're trying to find that sense of harmony, I think, in your skiing. Right, because you hadn't really been on snow that long and just trying to find that right feeling. And that's what I was doing and came over a little little knoll and then made a turn and my ski popped off in the middle of a turn. And all I remember is my ski popping off.

The first day of Christmas vacation, I went home. My brother and I went to Berkshire East and met up with a bunch of the buddies. We all skied with a group. It was a warm, sunny day. It was like a spring day, 20th of December, slushy snow, which was completely unheard of. And we took a couple of runs, as the coach said, and I was testing a new pair of skis - hadn't been on them yet. And we were going to run slalom and we came down and went back to the race track and he wasn't there. So we decided we'd take one more run. And it was just kind of a strange thing. You're trying to find that sense of harmony, I think, in your skiing. Right, because you hadn't really been on snow that long and just trying to find that right feeling. And that's what I was doing and came over a little little knoll and then made a turn and my ski popped off in the middle of a turn. And all I remember is my ski popping off.

How did your friends respond?

I was in shock. But my friend, a guy named Jim Schaefer who actually now owns Berkshire East, was the first one to me. My brother was there soon afterwards and I was just kind of lying on the ground and they were doing their best. It was obvious to them that I'd hurt myself pretty badly. So they were trying to keep me from moving and everything until the ski patrol could come up. I fell in the middle of the trail and didn't hit anything but the ground. It was just one of those weird falls. I probably had taken what I thought were much worse falls and had no problem. But this time, whatever I did, I did it in exactly the right or the wrong way, however you want to look at that.

I was in shock. But my friend, a guy named Jim Schaefer who actually now owns Berkshire East, was the first one to me. My brother was there soon afterwards and I was just kind of lying on the ground and they were doing their best. It was obvious to them that I'd hurt myself pretty badly. So they were trying to keep me from moving and everything until the ski patrol could come up. I fell in the middle of the trail and didn't hit anything but the ground. It was just one of those weird falls. I probably had taken what I thought were much worse falls and had no problem. But this time, whatever I did, I did it in exactly the right or the wrong way, however you want to look at that.

What was the outcome of your accident?

I broke thoracic 10 and 11. So there are 12 thoracic bones, there are seven cervical bones. And for me, I broke and really pulverized those two vertebrae. The doctor said it looked like a bad car accident. I was probably going 20 to 30 miles an hour, which doesn't seem fast when you're skiing, but when you fall, it can be fast. So that's what I broke. It corresponds to about belly button (level) as far as sensation. And I have the muscles just below the sternum and sort of corresponding back muscles. So when I started skiing in a monoski, I was in the most disabled of the three classes because I didn't have the ability to lean over onto my legs, like I'm sitting in my wheelchair to lean on to my legs and then sit back up. I don't have the muscles to do that. So once I'm leaning on my thighs, then I really that's where I am until I push myself up with my arms.

I broke thoracic 10 and 11. So there are 12 thoracic bones, there are seven cervical bones. And for me, I broke and really pulverized those two vertebrae. The doctor said it looked like a bad car accident. I was probably going 20 to 30 miles an hour, which doesn't seem fast when you're skiing, but when you fall, it can be fast. So that's what I broke. It corresponds to about belly button (level) as far as sensation. And I have the muscles just below the sternum and sort of corresponding back muscles. So when I started skiing in a monoski, I was in the most disabled of the three classes because I didn't have the ability to lean over onto my legs, like I'm sitting in my wheelchair to lean on to my legs and then sit back up. I don't have the muscles to do that. So once I'm leaning on my thighs, then I really that's where I am until I push myself up with my arms.

Despite your prognosis, how did you retain your passion for skiing?

I was back on snow within the year, 362 days after the accident. I thought about skiing. I did a fair amount of mental imagery when I was training for skiing. And there was nothing I could do while I was lying in the hospital bed. And I thought over and over about skiing. I thought, OK, I'll get back. I won't be healthy for the season, but maybe I'll be able to ski like maybe forerun the Middlebury Carnival, which was always the last race of the year. That's what I initially thought. Nobody told me that I was paralyzed.

I was back on snow within the year, 362 days after the accident. I thought about skiing. I did a fair amount of mental imagery when I was training for skiing. And there was nothing I could do while I was lying in the hospital bed. And I thought over and over about skiing. I thought, OK, I'll get back. I won't be healthy for the season, but maybe I'll be able to ski like maybe forerun the Middlebury Carnival, which was always the last race of the year. That's what I initially thought. Nobody told me that I was paralyzed.

What was the catalyst to get you back on skis?

I did believe that I, as an athlete, would be able to create a miracle and recover completely. But at the same time a friend of mine asked me if I would be willing to be in a movie about adaptive skiing, a documentary movie about adaptive skiing. And he asked me about this while I was in the hospital. I said, yes, sure, I will do that. A friend of his was making that movie. And so that to me was the plan.

I did believe that I, as an athlete, would be able to create a miracle and recover completely. But at the same time a friend of mine asked me if I would be willing to be in a movie about adaptive skiing, a documentary movie about adaptive skiing. And he asked me about this while I was in the hospital. I said, yes, sure, I will do that. A friend of his was making that movie. And so that to me was the plan.

Had you had any contact with adaptive skiers in the past?

Tom, you knew (Olympic disabled champion) Diana Golden, right? Diana was an amazing person. I saw her at a giant slalom at Burke Mountain the year before my accident. I saw Diana at this race and my first thought was: really? There's a woman with one leg who's coming to this race. But then I watched her ski. To me, she captured what it meant to be an athlete. As ski racers, it's really easy to have all of your excuses before you go through the starting gate. She was somebody who just said, 'look, I'm not going to make any excuses. I don't have time for excuses.' She laid herself bare effectively and just said, 'I'm going to fall down, but I'm going to get back up.' In watching her, I thought, that's the best encapsulation of what it means to be an athlete. I remember thinking, I want to be like Diana, I want to do what she did.

Tom, you knew (Olympic disabled champion) Diana Golden, right? Diana was an amazing person. I saw her at a giant slalom at Burke Mountain the year before my accident. I saw Diana at this race and my first thought was: really? There's a woman with one leg who's coming to this race. But then I watched her ski. To me, she captured what it meant to be an athlete. As ski racers, it's really easy to have all of your excuses before you go through the starting gate. She was somebody who just said, 'look, I'm not going to make any excuses. I don't have time for excuses.' She laid herself bare effectively and just said, 'I'm going to fall down, but I'm going to get back up.' In watching her, I thought, that's the best encapsulation of what it means to be an athlete. I remember thinking, I want to be like Diana, I want to do what she did.

Your pathway to success was very quick.

I actually graduated on skis from Middlebury -- full cap and gown procession. Then I hopped on a plane and flew to Durango for my first first really full-fledged team camp when I was a full time ski racer. So I made the team (2002 Paralympics), which was touch and go.

I actually graduated on skis from Middlebury -- full cap and gown procession. Then I hopped on a plane and flew to Durango for my first first really full-fledged team camp when I was a full time ski racer. So I made the team (2002 Paralympics), which was touch and go.

Early in your career, who helped to inspire you?

Jack Benedick was tougher than nails. I loved Jack. He scared me at times. And he said, 'you're on this team to win medals.' And I thought, 'OK, well, this is it. Like, I've been taking my lumps the whole season. Now I get to go beat up on some people. This is good.' And so I went into Albertville thinking, this is the fun part. This is going to be great. We raced as a team.

Jack Benedick was tougher than nails. I loved Jack. He scared me at times. And he said, 'you're on this team to win medals.' And I thought, 'OK, well, this is it. Like, I've been taking my lumps the whole season. Now I get to go beat up on some people. This is good.' And so I went into Albertville thinking, this is the fun part. This is going to be great. We raced as a team.

Your accomplishment in 1992 was stunning - winning all four medals in your class at the Lillehammer Paralympics just like Jean-Claude Killy.

Jean-Claude Killy was my hero in a lot of ways, I was born in 1968 when he won. He was my father's hero. And I thought, 'OK, this is it. I have a chance to do it.' I had said early on, I don't want to be limited by the disability. I don't want to be defined by the disability. I said I was going to be the fastest monoskier in the world. And to me, that's the definition of skiing. I needed to prove on the biggest stage that I could be the best in the world. In the downhill in Lillehammer, I realized that goal. I was the fastest mono skier in the world in the downhill. Lillehammer was really the pinnacle of my skiing career, realizing that goal and being the fastest in the world.

Jean-Claude Killy was my hero in a lot of ways, I was born in 1968 when he won. He was my father's hero. And I thought, 'OK, this is it. I have a chance to do it.' I had said early on, I don't want to be limited by the disability. I don't want to be defined by the disability. I said I was going to be the fastest monoskier in the world. And to me, that's the definition of skiing. I needed to prove on the biggest stage that I could be the best in the world. In the downhill in Lillehammer, I realized that goal. I was the fastest mono skier in the world in the downhill. Lillehammer was really the pinnacle of my skiing career, realizing that goal and being the fastest in the world.

What prompted you to move to Utah?

I moved to Utah in October of 1999. I thought, 'OK, with these games being here in 2002, I need to be part of that.' I need to be part of the buildup to the games.

I moved to Utah in October of 1999. I thought, 'OK, with these games being here in 2002, I need to be part of that.' I need to be part of the buildup to the games.

Did you see motivational speaking as a natural calling for you after your athletic career ended?

That's a really good question. It is funny, because if you ask me when I was in college, if I would be doing this stuff that I'm doing, I would tell you that you are absolutely crazy because I hated getting in front of a group. I mean, this is the sweaty palms, the shaking knees, the shaking voice. I hated it. Absolutely hated it. And there are a lot of things that I ended up doing that were in some ways, in some ways were vehicles for being able to tell the story that if I didn't have a story, I might not necessarily have done these things.

That's a really good question. It is funny, because if you ask me when I was in college, if I would be doing this stuff that I'm doing, I would tell you that you are absolutely crazy because I hated getting in front of a group. I mean, this is the sweaty palms, the shaking knees, the shaking voice. I hated it. Absolutely hated it. And there are a lot of things that I ended up doing that were in some ways, in some ways were vehicles for being able to tell the story that if I didn't have a story, I might not necessarily have done these things.

Do you think the Olympics and Paralympics can return to Utah in 2030 or 2034?

My experience in 2002 was the greatest experience that I've had in the Paralympics. The interaction with the people in Utah was just different than anything else I'd really seen. And we have the Greatest Snow on Earth. We have mountains all within an hour's drive of the airport. We have so many athletes who live and train here. It's a culture of sport. There are a lot of cities that are not interested where the people aren't really that interested in hosting the Olympics and the Paralympics. But the people here in Utah are. And I think it could be a great celebration of sport.

My experience in 2002 was the greatest experience that I've had in the Paralympics. The interaction with the people in Utah was just different than anything else I'd really seen. And we have the Greatest Snow on Earth. We have mountains all within an hour's drive of the airport. We have so many athletes who live and train here. It's a culture of sport. There are a lot of cities that are not interested where the people aren't really that interested in hosting the Olympics and the Paralympics. But the people here in Utah are. And I think it could be a great celebration of sport.

Listen in to Ski Utah's Last Chair episode with Chris Waddell to learn more:

- Which of his global accolades means the most to him.

- Challenges at writing children's books.

- His attempt at becoming a comedian.

- His views on polygamy.

- Recognition by the Dalai Lama.

- His view on moguls vs. powder.

Tune in to Last Chair: The Ski Utah Podcast presented by High West Distillery on your favorite podcast platform. Subscribe to get first access to every episode.

Join our newsletter

The Utah Ski and Snowboard Association is a non-profit trade organization founded in 1975 with the aim of promoting Utah's ski and snowboard industry. Our membership represents resorts, lodging, transportation, retail, restaurants and other ski and snowboard related services. The Utah Ski and Snowboard Association is governed by a 21-member board of directors elected from its membership.

Learn More About Ski Utah the bennefits of joining the Ski Utah membership.

Copyright Ski Utah